The rocky launch of the Department of Health and Human Services' HealthCare.gov is the most visible evidence at the moment of how hard it is for the federal government to execute major technology projects. But the troubled "Obamacare" IT system—which uses systems that aren't connected in any way to the federal IT infrastructure—is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the government's IT problems.

Despite efforts to make government IT systems more modern and efficient, many agencies are stuck in a technology time warp that affects how projects like the healthcare exchange portal are built. Long procurement cycles for even minor government technology projects, the slow speed of approval to operate new technologies, and the vast installed base of systems that government IT managers have to deal with all contribute to the glacial adoption of new technology. With the faces at the top of agency IT organizations changing every few years, each bringing some marquee project to burnish their résumés, it can take a decade to effect changes that last.

That inertia shows on agency networks. The government lags far behind current technology outside the islands of modernization created by high-profile projects. In 2012, according to documents obtained by MuckRock, the Drug Enforcement Agency's standard server platform was still Windows Server 2003.

Magnifying the problem is the government's decades-long increase in dependency on contractors to provide even the most basic technical capabilities. While the Obama administration has talked of insourcing more IT work, it has been mostly talk, and agencies' internal IT management and procurement workforce has continued to get older and smaller.

Over 50 percent of the federal workforce is over 48 years old—and nearly a quarter is within five years of retirement age. And the move to reliance on contractors for much of IT has drained the government of a younger generation of internal IT talent that might have a fresher eye toward what works in IT.

But even the most fresh and creative minds might go numb at the scale, scope, and structure forced on government IT projects by the way the government buys and builds things in accordance with "the FAR"—Federal Acquisition Regulations. If it isn't a "program of record," government culture dictates, it seems it's not worth doing.

Hell is a 1.5 million user installed base

Slow technology adoption is nothing new. In 1992, I was working as a contractor for the US Army Test Lab at Aberdeen Proving Ground, installing a batch of new PCs purchased under the Department of Defense's Desktop IV contract from Unisys. The PCs, built by Unisys specifically for the contract, came loaded with Windows 3.1; it was my job as the network engineering support manager to ensure that the hard drives were reformatted and loaded with Microsoft DOS 3.31—the standard supported operating system.

The hazards of running an operating system more than 10 years old, however, go beyond having a pretty user interface. The government has kept using Windows XP and Server 2003 despite warnings from the National Security Agency that "Windows XP and Windows Server 2003 lack critical security features and are near the end of their extended support lifecycle." Still, the federal government (much like most of the business world) largely took a pass on Windows Vista. And even though the National Institute of Standards and Technology added Windows 7 to the US Government Configuration Baseline a year after its release, most agencies didn't start migrating off Windows XP until 2011 or later. While the Army and Air Force had adopted Windows Vista, XP was still fairly widespread when the Army began migrating to Windows 7 in July of 2012.

That's not to say that the DOD hasn't tried to make its IT more modern and efficient—the DOD has long been among the government's IT "haves," at least budget-wise, and the military is counting on IT efficiency to help reduce costs. But the scale of the changes it has to make in those efforts is staggering, and the process takes years to implement.

The US Army's Enterprise Email (EE) program is a case in point. EE, which the DOD's CIO calls "Army's #1 information technology efficiency initiative," is a unified e-mail system for the DOD. The Army, its first customer, had over 440 separate networks—each of them with their own e-mail systems and directories on a variety of different software platforms—when it started looking for an Army-wide solution in 2009. The Army gave up on trying to find its own answer and turned to the Defense Information Systems Agency. The agency, which is in essence the DOD's internal IT and telecommunications provider, started rolling out its internally built system based on Microsoft Exchange to the Army in February of 2011.

The migration was finally (mostly) completed in July, two-and-a-half years after it started, after a few fits and starts (and a Congressionally mandated cooling-off period). It now reaches over 1.43 million users on the Army's unclassified network, and 115,000 on the secret SIPRNET network. That's a tiny fraction of the over 425 million users that Google serves with Gmail, but it's the biggest Exchange deployment outside of Microsoft's Office 365 cloud—and it all has to run within the DOD's security specifications on DOD hardware.

In other places, it's not so much an installed base of hardware as it is an installed culture. Conway's Law is in full effect on many government IT projects (hat tip to Bruce Webster for reminding me of Melvin Conway's pearl of truth). That principle, as stated by Conway in an article published in Datamation in 1968 entitled "How Do Committees Invent?" asserts:

Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization's communication structure.

Considering the highly codified and byzantine communication structure of most government agencies and the stylized method of communications that agencies and contractors engage in to procure and define IT projects, it's amazing that anything ever gets done by government IT organizations—and that their systems work at all.

Declaring victory

Even when a big rollout "succeeds"—as in hits its numerical goals—it's more often than not a dirty victory, if not a Pyrrhic one. EE again is a case in point: all its users have not exactly greeted it joyfully.

On a post on the Army CIO's blog regarding the progress of the rollout of EE, the comments from the field were almost universally negative. One reservist bemoaned the replacement of the already barely tolerable Army Knowledge Online webmail system with EE on it (one of many expressing user rage):

With EE I have lost the ability to check my email on mobile devices (like iPhone). EE asks me to enter my (Common Access Card) PIN multiple times per session. The GAL (global address list) and my contacts often crash when doing a lookup. Right now I am trying to send something… and the systems seems to be down.

We have become so dependent on email for communications and the new enterprise email does nothing but degrade this capability. It's just plain unstable and not ready for prime time. On the civilian side I am a software engineer. My customers would NEVER accept such horrible service. Unfortunately we are forced to live with it (along with a ton of other shoddy applications DOD buys).

An Army IT person expressed even more outrage, calling parts of the new system "a crime against humanity":

I worked in a major NEC during the Enterprise Email migration and I can tell you it is nothing short of a catastrophic failure. It is unreliable, it causes Outlook to hang and crash routinely, and messages are severely delayed or outright lost with no explanation...

The reason you and all other [senior executive service] and [general officers] think it is a success is because somewhere a room full of guys like me are bending over backwards to make sure that you guys get the absolute best possible service and that even the slightest hint of a glitch is taken care of before you ever even think about noticing it. You guys are likely on your own dedicated servers to make sure you don't have any resource problems, or at the very minimum your accounts are moved to the Exchange servers deemed to be the most reliable. You never see any of this action, and your subordinates won't dare tell you it's happening, but you can rest assured that it is. Meanwhile, all the rest of us are left to fend for ourselves on an overworked and unreliable infrastructure that is crumbling under its own weight.

Or, as one other commenter put it: "SSDD."

Measuring the wrong thing

The same comments could be posted on nearly any federal CIO's blog (if they dared to have one, and if they allowed comments like the Army CIO/G6 office does). But most of the systems they complain about don't have the sort of public exposure that HealthCare.gov has. Part of the reason is the metrics that the government uses for "success" in its IT programs and part is how they get bought in the first place.

The DOD CIO's IT Dashboard entry for EE rates it as a top program with a metrics score of 5 out of 5. But the Army hasn't begun to measure one of its key metrics—the speed of mail delivery. And service availability, rated at 99.998 percent, is measured based on "a collective average using the Exchange servers in all the pods"—not on the user experience.

There's a similar disconnect in metrics over at the Department of Health and Human Services. Take the HealthCare.gov Plan Finder program, part of the HealthCare.gov site that, as described by HHS' project dashboard, is "a portal that allows consumers to search for both public and private health coverage options through an easy to use health insurance finder tool. Based on answers to a series of questions, the coverage finder produces a menu of potential coverage choices personalized for the user."

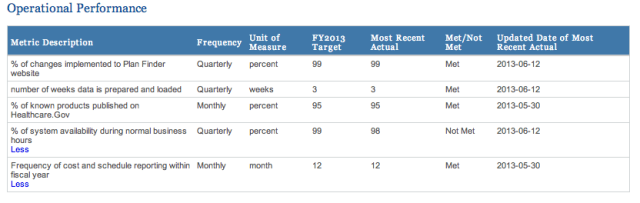

According to the IT Dashboard, "CMS updated the outstanding issues with the Performance Metrics on August 29, 2013. The CIO Rating is currently at 5." That's the top performance rating a CIO can give a program. But here are the metrics that score is based on:

Many of these metrics might seem like pointless measurements for a greenfield project like HealthCare.gov. Since it’s a new system, achieving 99 percent of the changes to the website is not exactly a banner note. And the one metric not met is "percent of system availability during normal business hours," measured per quarter—before the site was even online to the public.

The bottom line is that federal IT programs' success is measured by things that have nothing to do with how successful they are or by the metrics most of the world uses. While the business world (and Web companies in particular) now monitor user experience and productivity as a metric for IT success, the government keeps throwing out numbers that mask the truth: the only people who would use their systems are the ones that are forced to.

Like people who need health insurance.

Listing image by Kasper Duhn

reader comments

165