The Genachowski-led Federal Communications Commission (FCC) seems to delight in dropping bombshells on a weekly basis, but we didn't see this one coming: the FCC admits that its CableCARD mandate has been an abysmal failure. That doesn't mean it's giving up the fight to encourage set-box box innovation; instead, the FCC wants ideas for a new set of rules that will bust open access to video streams from cable and IPTV operators.

Call it "Son of CableCARD"... and rest assured, the cable industry ain't gonna like it.

Total failure

If you're curious how an agency like the FCC says something like "total failure," take a look at yesterday's innocuously titled document, "Comment sought on video device innovation." Buried inside that document are these lines: "The Commission's CableCARD rules have resulted in limited success in developing a retail market for navigation devices. Certification for plug-and-play devices is costly and complex."

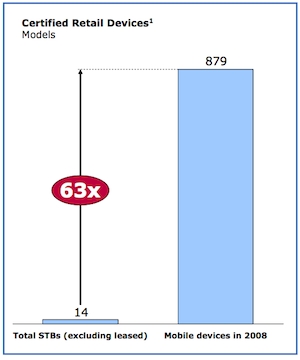

"Limited success" is a bureaucratic euphemism for abject failure, as the FCC made clear during its own November open meeting. During that event, as part of its discussion about the National Broadband Plan, it noted that set-top box innovation had stagnated. Agency engineers showed the following chart, pointing out that only 14 non-leased set-top boxes were on the market in the US.

Fourteen—and yet most Americans own a TV, and most subscribe to some form of pay-TV service. Compare this to mobile devices, where innovation has exploded despite (the now loosening) carrier restrictions; in 2008, 879 mobile devices were in existence. Why innovation in the one market but not the other?

CableCARD was the government's attempt to open up the "navigation" market for video content, allowing third-party televisions, DVRs, and set-top boxes to access and control cable video streams. What the FCC wanted was innovation of the kind seen in other video products like the TiVo, the Roku box, the AppleTV, the Xbox 360, and the PS3. All were essentially "set-top boxes" that did all manner of cool things, including access video content over the Internet from sites like Netflix. What none of them did was integrate content from cable companies, which would have made them even more innovative and far more useful.

CableCARD was supposed to be the fix, but it was slow to deploy, was never widely supported, and had huge limitations. Early versions of the host spec supported only one-way access, so electronic program guides, video-on-demand, and other two-way services didn't function. The FCC then tried to force the industry's hand, all but demanding innovation by requiring cable operators to use CableCARDs even inside their own leased set-top boxes, just to level the playing field.

But the "integration ban" didn't help much, either, as the cable industry delights in pointing out every time it submits a status report on CableCARD. After years in the wild, nearly all CableCARD deployments at the moment are in cable-owned set-top boxes, and third-party devices like the Roku box and Sony's PS3 never bothered with them. (Most of the rest are in TiVo DVRs.)

If at first you don't succeed, try tru2way

The situation wasn't good for anyone. Innovation wasn't happening and cable operators complained endlessly that the integration simply made their set-top boxes more costly for no real reason.

So the industry pushed tru2way, the successor technology. Tru2way features, as the name suggests, real two-way operation. It still uses a CableCARD for security, but the navigation code now runs on a middleware Java-based stack inside devices like TVs. The cable industry has signed on many consumer electronics vendors, but despite a couple years of hype, it's nearly impossible to buy and use a tru2way device.

Still, they're coming, and cable operators are moving forward with headend rollouts to support the tech. Once those are live, a user with a tru2way TV set can move anywhere in the country, plug into the local digital cable system, and have full two-way access without a set-top box. So why doesn't this make the FCC happy?

Real innovation?

The short answer is that tru2way makes "convergent innovation" of the kind the FCC wants to see difficult or impossible. For instance, imagine what a device like an Xbox 360 or a PS3 could do with access to cable video streams. It could offer onscreen e-mail alerts over TV shows, provide one-click access to further stats during sports games, function as an HD DVR, etc. The possibilities from this sort of convergence seem awesome and nearly endless.

But, says the FCC, "the tru2way license requires device manufacturers to separate cable navigation from all other functions that the device performs. On the other hand, devices like TiVo, Moxi, Microsoft's Xbox 360, AppleTC, Roku, Sony's Playstation 3, and Vudu each use a consistent menu as they navigate through video content regardless of its source."

The agency now seeks comment "on how to encourage innovation"—that is, what it should try next.

What's really being pushed for here? Hard to say, and it's not clear that the FCC has any preferences at this point. In the end, it may turn out that loosening up the tru2way licensing agreement will be enough, though device makers have never been very thrilled about having to allow a middleware stack created and controlled by the cable industry on their devices in order to access cable content.

Disrupter-in-chief

All we can say is "wow" at this point. The Genachowski-led FCC has been relentless in its effort to disrupt the status quo. In office for six months, Genachowski and team are drafting a national broadband plan; working on net neutrality rules; fingering companies like Google, Apple, and Verizon; dealing with spectrum reallocation; handling the nuts-and-bolts of white space device deployment; threatening to extend neutrality rules to wireless networks; and considering the transition from traditional circuit-switched phone networks to a full-IP communications network. Now, we can add "shaking up the cable industry" to the list.

Looking at the topics taken up so far, each is big-picture, disruptive, and pro-network openness. None are particularly radical; indeed, each idea simply develops programs and policies decided on by earlier FCC administrations, some of them Republican. Network neutrality builds on the Internet policy statement, open access rules on wireless follow from the open access rules on the 700MHz spectrum auction, and the new TV initiative builds on the decade-old CableCARD push. The National Broadband Plan, which is new, was mandated by Congress.

So Genachowski doesn't seem to be a radical, but he does appear to be both relentless and ambitious in his quest to see these ideas carried through to their maximum potential for disruptive innovation. And he's not above irritating just about every major incumbent with a network to do it.

Update: The cable industry says that it welcomes the idea, it just wants to make sure it goes even further by applying equally to all TV operators (which now includes companies like DirecTV, AT&T and Verizon).

"A Notice of Inquiry working to develop fresh approaches—especially approaches that cross multiple industry lines—should be pursued in concert with Commission policies that promote competition, innovation and other pro-consumer benefits,” said National Cable & Telecommunications head Kyle McSlarrow.

Cable certainly can't be interested in ditching all of its work on CableCARD and now tru2way, so we're curious to see how this plays out.

reader comments

72